The fatigue

Fatigue is a complex and multifactorial process that affects performance. Neither the way fatigue occurs nor the hierarchy of factors that cause it in any of the production modalities is still not completely known.

In this series of articles we deal with some of the most important concepts of strength training, collecting notes from the recently published book Strength, Speed and Physical and Sports Performance written by renowned researchers Juan José González Badillo and Juan Ribas Serna.

Summary

- Fatigue can be defined as any situation in which the value of muscle activation is inevitably and involuntarily decreased.

- The feeling of fatigue increases faster than the amount of work done in the unit of time to protect the body from possible injury.

- Without fatigue there would be no possibility of improving performance, because the adaptation processes would not take place. The challenge is to reach the degree of fatigue with which to obtain the best results.

Observations related to fatigue range from the will to perform specific acts to changes in the behavior of intracellular proteins. In general, it could be conceptualized as the inability to continue a task at a stipulated level (usually stipulated by the central nervous system).

The difficulty in understanding the production of fatigue derives from numerous factors: places where it can originate, the different methods that must be used to measure the effects of fatigue, the difficulty in extrapolating in vitro results to situations in normal or physiological conditions or difficulty in integrating all the results.

The feeling of fatigue increases faster than the amount of work done in the unit of time (Mosso, 1904), thus protecting our body from possible injuries of lesser or greater severity.

Thus, fatigue is largely an emotion, part of a complex regulatory system that keeps us from taking risks. In extreme conditions, in which the will ignores this emotional indicator, tissue damage occurs and, in very extreme cases, death.

We have examples of this every day in endurance competitions such as the marathon, which precisely commemorates the death of a soldier (Philipides) who, ignoring his fatigue, insisted on continuing to run until he exceeded the limits of the regulation systems and died after deliver important news.

The feeling of fatigue increases faster than the amount of work done in the unit of time

Our brain uses fatigue symptoms as a key regulator to ensure that exercise is stopped before bodily harm is done. However, among the symptoms of fatigue, the “sense of effort” stands out.

This feeling of exertion increases as more repetitions of a task are performed, until just one more repetition is an extreme effort. This sensation of effort is proportional to the difference between the task commanded by the nervous system and the real difficulty in carrying it out.

For its part, the difficulty in carrying out a task will depend on many mechanical, physiological and biochemical variables at different levels from muscle cells to the organs in charge of general homeostasis. This sensation of effort is modulated to a certain degree by the will of the athlete.

For individuals with the same level of training and performance, the differences between winners and losers sometimes only includes the mental decision, the will, different in the winners.

Fatigue is synonymous with a wide range of physiological conditions, from pathology and general health to sport and exercise (Wilkinson et. al., 2010). Fatigue in sport and physical activity in humans has usually been described in subjective terms and has been measured by the acute reduction in physical performance during and after exertion.

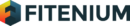

The consequence of exercise-induced fatigue is the inability to maintain a certain value of applied force, which results in loss of speed and power of execution in dynamic actions. It is considered that there are three factors through which fatigue is expressed in mammalian muscle:

1) reduction in the number of active cross bridges, which affects the loss of isometric strength,

2) reduction of the maximum speed of muscular shortening in activations without opposition to the shortening (absolute speed) and,

3) increase in the curvature of the force-velocity curve that affects the reduction of maximum power (Jones, 2019).

For individuals with the same level of training and performance, the differences between winners and losers sometimes only includes the mental decision, the will, different in the winners.

Therefore, fatigue is quantified by the loss of strength, muscle shortening velocity, and force production in unit time (RFD). Loss of static or isometric strength depends on reducing the number of active cross bridges (pc) and the force exerted by each pc.

The loss of speed and RFD depends on the decrease in the rate of formation and activation of pc. As a consequence of the loss of strength and speed, power will decrease. A phenomenon associated with the above that affects them is the deactivation rate of the pc, which is a determining factor in the relaxation time and in the rate of formation of the pc themselves.

However, the physiological mechanisms prior to the final consequences that we have just indicated, and that underlie fatigue, give rise to different proposals and are still the objective of numerous investigations.

The causes of fatigue may be related both to the oxygen transport capacity and the available metabolic substrates, as well as to the cerebral causes of the contractile fibers of skeletal muscle and the muscle activation mechanisms themselves. Therefore, the decrease in force / speed associated with fatigue can originate in any process at different levels, from the brain order to the formation of actin-myosin cross-bridges (Debold, 2012).

But in practice, to study fatigue it is necessary to specify the task and the production mechanism. Otherwise it would be, if not impossible, if not very complex, to study all the elements that can intervene in the generation of fatigue simultaneously. For example, the speed and extent with which fatigue occurs depends largely on the type and intensity of the physical activity performed (Fitts, 1994).

But the main purpose is not to discuss the different opinions regarding the causes of fatigue or the methodologies used to detect and measure them, but to expose the most accepted ideas, although also discussed, and that have a practical application for physical and sports performance. .

fatigue concept

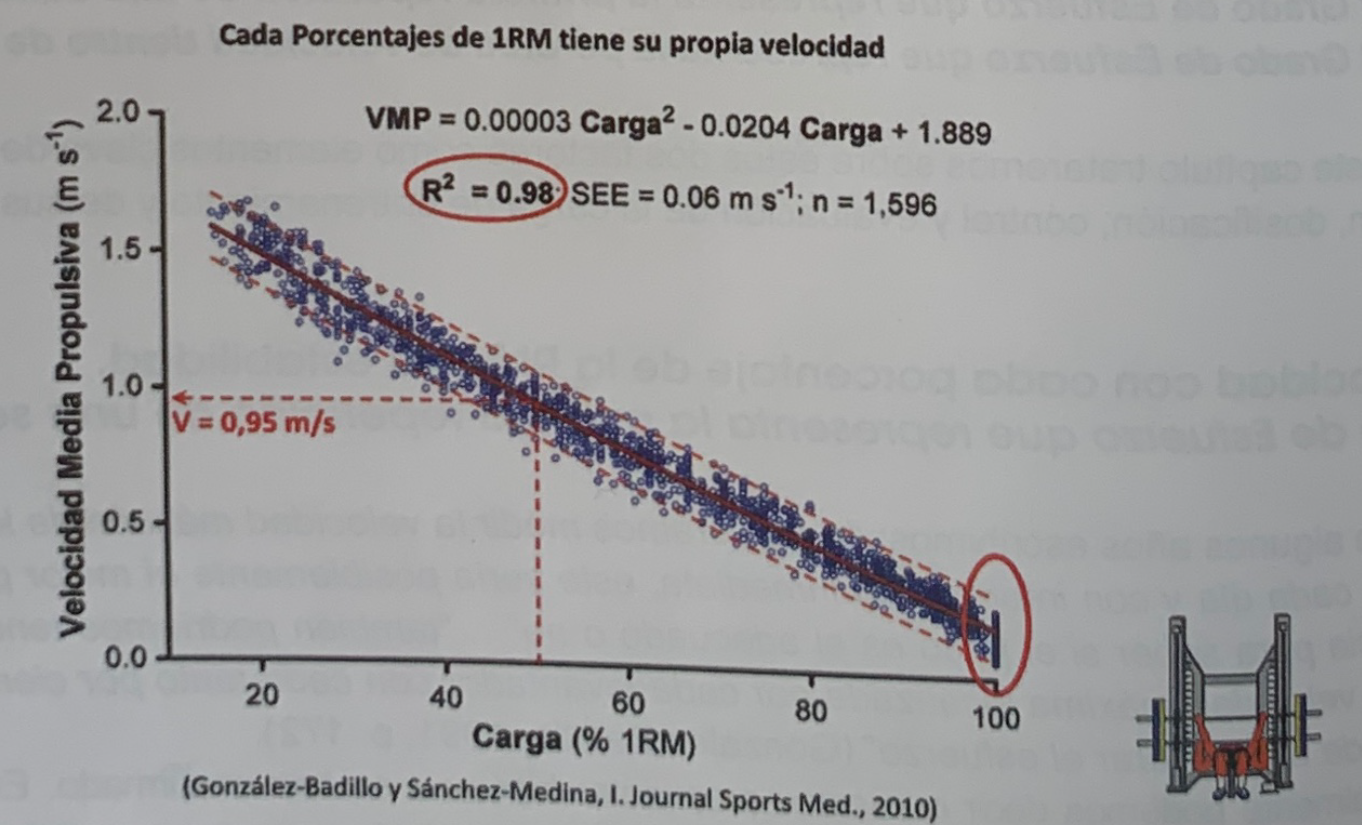

Fatigue can be defined as any situation in which the value of muscle activation is inevitably and involuntarily decreased. (loss of force, production of force in the unit of time or RFD, speed, power,) with respect to another value reached in a time immediately prior to the effort. In this sense, Macintosh and Rassier (2002) define it as a contractile response that is less than what is expected for a given stimulation. It can also be expressed as the inability to maintain a certain intensity (speed or power) over time.

And it can also be defined and differentiated by the recovery time after the effort. Fatigue can begin in the first moments after the muscle activation command is initiated or from the first effort in a series of repeated efforts, without the need for muscle failure or the inability to maintain a certain intensity.

Therefore, the most relevant and appropriate way to define fatigue is to consider it as the magnitude and time of loss of performance in whatever the situation may be in relation to what is programmed or intended by the will or the CNS. From these definitions the need to know the value of contraction or performance prior to the measurement of fatigue can be deduced. Therefore, the conditions that must be met for us to be in a position to quantify fatigue are that there is loss of performance, that this loss does not occur voluntarily, and that there is a previous value that is taken as a reference.

In the Essential Dictionary of Sciences, fatigue is defined as the deterioration of the performance of a living being… over time. It is associated with a feeling of tiredness, lack of concentration, slowness and the appearance of simple errors. But a muscular activation, in addition to fatigue, can also produce potentiation, which is an opposite response to fatigue, whereby an increase in muscular performance is produced as a consequence of an immediately previous activation. Therefore, fatigue and potentiation can coexist.

The possible existence of two opposite effects in the same muscle activation makes it difficult to determine the degree of fatigue. In this situation, great care must be taken in the interpretation of the data referring to a “before” and an “after”: the result can be a mixture of fatigue and potentiation.

However, potentiation has a limited duration while fatigue may persist until functional incapacity. Even when the post-effort performance is greater than the initial response, there is no guarantee that the mechanisms associated with fatigue are not present (Macintosh and Rassier, 2002).

a muscular activation, in addition to fatigue, can also produce potentiation, which is an opposite response to fatigue, whereby an increase in muscular performance is produced as a consequence of an immediately previous activation.

In this way, we can find situations in which the response is greater than that which occurs in the resting state (potentiation), but probably less than what could be expected if there were no fatigue. In fact, In training practice, it is observed that when the efforts are not made until exhaustion, the response after the effort (for example, measured through the vertical jump) in some cases is superior to that offered before it., even having previously warmed up to reach maximum initial performance.

That is, the effort has meant a “better warm-up” than the one previously made. But there are also situations in which the contractile response is less than before the effort. If this is the case, it can be concluded that fatigue exists with certainty, but its quantification is not easy, because there are also potentiation mechanisms simultaneously. This means that if the potentiation mechanisms were not present, the magnitude of the fatigue measured would be greater.

The term fatigue should not be identified with situations in which one becomes exhausted, with a forced interruption of the activity. Muscle fatigue begins immediately after starting physical activity and includes changes in physiological processes that reduce muscle strength (Enoka, 2002).

fatigue and training

Fatigue must be considered as a component of training, and therefore, it must also be considered as an essential character of the stimulus necessary to ignite the adaptation processes of training. The degree of fatigue (subjective, observed by the coach, or measured through the relevant means) is the reference point to determine and assess the training load. Without fatigue there would be no possibility of improving performance, because the adaptation processes would not take place. The problem that arises is the degree of allowable fatigue to achieve the best result, or how training makes us more resistant to fatigue.

Without fatigue there would be no possibility of improving performance, because the adaptation processes would not take place. The problem that arises is the degree of fatigue that is acceptable to achieve the best result, or how training makes us more resistant to fatigue.

degree of fatigue

Overload is a situation in which the subject is subjected to a stimulus (load) higher than usual. In order to produce fatigue, it is not necessary for overload in this sense, but other minor stimuli than the usual ones can also cause fatigue. Depending on this degree of fatigue and its duration, we find ourselves in three different situations:

i) acute or immediate fatigue of short duration (from a few minutes to a few hours or 2-3 days)

ii) fatigue of medium duration (from several days to 2-3 weeks) and,

iii) long-term (chronic) fatigue (several weeks to several months)

Acute fatigue corresponds to the fatigue produced by an exercise (a series or repetition) or a training session. Recovery should occur before the next set or repetition (in full or in part) or before the next session (in full).

Medium duration fatigue is the fatigue produced intentionally by several training sessions. It is made up of several units of acute fatigue without sufficient recovery between sessions. After several training units, a special, broader recovery occurs. It is expected that from this sustained load phase a higher supercompensation phase will emerge, which corresponds to the English term “overreaching”, for which there is no equivalent term in Spanish. but if the consequence is that optimal supercompensation is not reached, the subject is considered to be in an “overloaded” situation, or with excessive fatigue.

Chronic or long-term fatigue does not occur on purpose. It is the consequence of an error in training programming, although it can sometimes be associated with other circumstances such as certain diseases. It is caused by carrying out an excessive number of fatigue phases of medium duration. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between the phase of medium and long duration fatigue. Recovery from this state of fatigue may take several months. It corresponds to the English term “overtraining”, which in Spanish would be equivalent to the term “sobretraining”.