What happens if I can’t measure the speed?

No one doubts the importance of speed measurement for precise control of training dosage and evaluation of its effect. But surely many have wondered, what do I do if I can’t measure the speed? (note: it is better not to measure it than to measure it wrong),

In this series of articles we deal with some of the most important concepts of strength training, collecting notes from the recently published book Strength, Speed and Physical and Sports Performance written by renowned researchers Juan José González Badillo and Juan Ribas Serna.

SUMMARY

- If speed cannot be measured, the best procedure is to subjectively estimate it by observing the ease/difficulty of performing the movement.

- When you notice an increase in playability (increase in speed), you should increase the absolute load a bit and wait for the speed to increase again with this new load.

- You can also apply the procedure to check if the subject is in the average, above or below the population in terms of the number of repetitions can be done with each percentage of the RM.

The most direct answer to the question would be: “if you cannot measure the speed, estimate it subjectively by observing the ease / difficulty of the execution of the movement”. In the 1970s and 1980s this was already considered necessary and the best way to adjust the training load, and these ideas were subsequently published: “If you can’t measure speed accurately, you have to judge it subjectively: you have to Observe the fluidity of the movement, the coordination, the ease to fix the bar, to recover in the clean and in the snatch, the greater or lesser elevation of the bar, the speed / ease of take-off…” (González-Badillo, 1991).

if you can’t measure the speed, estimate it subjectively by observing the ease/difficulty of executing the movement

This is really the best way to supply the execution speed measurement as a reference. Naturally, in order to roughly estimate the relative load, that is to say, the displacement speed represented by a weight, it is necessary to have some experience.

The best thing to do is to start estimating speed from the first sessions, to remember how to do it you can consult this note which explains how you can start training the squat from the beginning of the training practice.

In this article it is indicated that the observation of the changes in the ease / speed of execution of the exercise has to be the reference to gradually increase the absolute load, without the need to measure the speed. Since we would start with a very light load, which can be moved very easily or with high absolute speed, maintaining this ease of execution or slightly less, while increasing the absolute load, can allow us to train for a long time with a guaranteed improvement in performance. performance.

The key points of training if speed cannot be measured are:

- That the execution difficulty increases slightly, although it should increase, and

- May the absolute load continue to grow.

The “image” of the difficulty / ease of execution (speed) must be recorded in the technician’s mind, to assess to what extent it evolves. The evolution must be one of continuous small changes: increases and decreases in speed, in accordance with the periodic incorporation of higher absolute loads.

The longer the same speed can be maintained or recovered in successive load increases, the more positive the training will be, although, necessarily, the speed will tend to be less each time, because the absolute load that is applied each time must represent an intensity somewhat higher, but the slower this increase can be in relative terms, the better.

In the same way, the greater the increase in absolute load could be for the same increase in relative load, the greater the performance improvement will have been. When it is observed that this procedure is not enough to improve the speed with the weights with which you train, you can think about adding some weight and training at a slightly lower speed, higher relative intensity, as the maximum load of the session.

If the moment arrives in which the subject has already improved his strength enough and it is considered that he should or would need, given the strength needs in his sport, that the training loads be medium or high, a new procedure could be introduced, such as It would be to estimate how many repetitions the subject can do with a certain load (weight). This estimation is not made by reaching the maximum number of repetitions possible in the series, but leaving, according to the observer’s estimation, between 2 and 6 repetitions to be done.

The greater the number of possible iterations that you want to estimate, the more iterations you can leave undone.

The procedure would be as follows. If, for example, you want to know what is the load with which the subject can do 12 repetitions, which would be equivalent, on average, to 65% of the RM in the squat, the subject starts doing 8 repetitions with a small load. If, once the signal is finished, the trainer observes that the subject could do many more than the 8 repetitions performed, which is what should happen, because the load must be initially small, after a rest (about 3 minutes), it goes up. load a little and repeat the series of 8 repetitions.

If it is observed that you could still do more than 12 repetitions, for example, 16-18 repetitions, after a rest the load is increased again. If with this new load it is estimated that after doing the 8 repetitions he could do 4-5 more, it can be considered that this is the load with which the subject could do about 12 repetitions.

Once this is done, it would be best to train with half or slightly less than half the possible repetitions in the set (4-6 repetitions) with the selected load, depending on strength needs and training experience. Taking this load as a reference and observing how the difficulty / ease of execution evolves, enough sessions can be done with an acceptable control of the degree of effort made by the subject and the effect of the training.

When you notice an increase in playability (increase in speed), you should increase the absolute load a bit and wait for the speed to increase again with this new load.

As explained in the previous paragraph, when appreciating an increase in ease of execution (increase in speed), you should increase the absolute load somewhat and wait for the speed to increase again with this new load. After 4-6 weeks, if necessary, a trial could be done to select a new load that could be done fewer times or the same 12 repetitions.

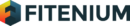

Choosing to be able to do more or fewer repetitions in the series means that you want to train with less or more relative intensity: the fewer possible repetitions, the greater the relative intensity. Each relative intensity (percentage of the MRI) can be done on average a maximum number of times in the series, which serves as a reference to estimate the relative intensity, but this has an error or always low, since, as is known Given the same relative intensity, the number of repetitions that each subject can do can be sufficiently different so that the percentage can range up to 10% in some cases.

In parallel, the procedure can be applied to check if the subject is in the average, above or below the population in terms of the number of repetitions he can do with each percentage of the RM.