Brief history of programming over time

This article reviews the most relevant theories in the history of training programming since it has been known and its key points.

In this series of articles we deal with some of the most important concepts of strength training, collecting notes from the recently published book Strength, Speed and Physical and Sports Performance written by renowned researchers Juan José González Badillo and Juan Ribas Serna.

In many cases, the practical experience of the coaches continues to be used as a reference and explanation of the training problem: “this has gone well for me and this is what has to be done”. This statement is not of a scientific nature since it does not try to find the causes that have caused a certain performance. But the strength of the good result is too important to accept another alternative, no matter how well founded it may appear to be.

It is quite common to find coaches who achieve good results and confess that they really do not know why one thing or another works for them. The only reason is that it “works well” (at least on some occasion). This approach will probably never end. We all act —consciously or unconsciously— under the umbrella of a theory, “our theory”, which supports us and justifies us —for us personally— the decisions we make when faced with any training problem.

In fact, in sport you act to a large extent based on conjectures, which you have to tend to confirm. Many of those that are considered the “theoretical bases” of training and that are currently applied have not been scientifically proven, so, from a scientific point of view, they should be considered more as hypotheses (often not even substantiated) than as theories.

In practice, it is usually considered as theory “what a famous coach says and writes, usually a foreigner”. Above all, his “theory” is followed, he agrees and “confirms” what we do and say. This usually creates “a theoretical body” that has never been subjected to scientific verification. This has been and is the situation in many cases. It must be recognized, however, that this -not finished- stage of the development of sports training has been very fruitful and has given rise to reflection on the fact of sports training. It is probably a necessary and natural stage through which the scientific knowledge of an object of study has to pass.

The science of human physical behavior is currently not in a position to provide an answer to most training problems. Generally, technicians act by intuition and elementary logic and obtain results, while science tries to find explanations for what is happening. Until reaching the current conceptions, which are not necessarily correct, a long way has been traveled in the knowledge of training, the main contributions of which are presented below.

The idea of scheduling or structuring sports training already appears in ancient Greece with the Tetra

The idea of scheduling or structuring sports training already appears in ancient Greece with the Tetra. The Tetra, or four-day plan, determined the training sequence. On the first day, light work was carried out, followed by a day with a high-load work, another very light one, and ending with another with a medium load. The participants in the Olympic Games had to train for about 10 months and do some competition practices before the arrival of the games.

Subsequently there is a long stage in which sport has little relevance in society. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the preparation time for athletes was 2-3 weeks, and 5-6 weeks was considered a very long time. A few years later, in 1916/17, Kotov proposed the need to carry out the training uninterruptedly and divided it into more or less differentiated cycles: general, preparatory and special training. He advocates a sports universalism without completely rejecting specialization.

In 1922, the Russian Gorinexskii was strongly opposed to “sports universalism”: you cannot practice all sports and compete in all. This prevents the improvement of sports performance. However, it admits that the general and harmonious development of the athlete is a necessary condition for sports specialization.

Shortly after, Birsin tries to conceive the training from the perspective of the laws that are observed in the development of the organism: the intensity must be raised until reaching an optimal load, fatigue It is not a biological phenomenon detrimental to performance and a rational alternation of loading and recovery must occur. It proposes a general stage and a special stage, with the need to increase the intensity in the special stage. On the same dates, L. Mang proposes training throughout the year, that the objectives of body and technical conditioning be carried out simultaneously and that athletes compete 20-30 times a year.

Gorinexskii: you cannot practice all sports and compete in all.

In 1930m the Finn L. Pihkala proposed a series of rules, some of which could still be considered valid:

- The alternation of charge and recovery,

- Undulating rhythm of the charge for days, weeks, months and years,

- The load should progressively decrease in volume and increase in intensity,

- All specific training must be based on a broad general physical condition,

- Includes a 3-4 month recovery period.

In 1939, the Russian Grantyn collected the ideas generated from the late 20’s and early 30’s and tried to state the essential features of what would later be known as “periodization” of training: he divided the training cycle into three periods: 1) the preparation, 2) the main one and 3) the transition one.

The first to create the conditions for specialization, the second for learning and improving the technique, application of specific loads, achievement and maintenance of sports form, and the third for recovery. It does not determine the duration of the periods because it thinks that they can be very different depending on the sports specialties. It can be considered that the training is already uninterrupted because the rest time is minimal.

Grantyn outlines the essential features of periodization

In 1946, Dyson proposes five periods from September to August in the preparation for specialists in athletics:

- Without competitions (preparatory) September to March 6 months,

- Pre-competitive (special preparation begins) (March),

- Medium level competition (to achieve optimal sports form) (May to mid-June),

- Of main competitions (mid-June-July), and

- Post-competitive (mid-July end of August).

In 1949, N.G. Ozolin, proposes a series of ideas:

- Detailed plans in stages and weekly cycles and their relationship with each period,

- During the transition period, training must not be interrupted or training changed to another discipline,

- The training process is presented as a year-round specialization based on multi-purpose body training (here an apparent contradiction between “year-round specialization” and “based on multi-purpose body training” arises).

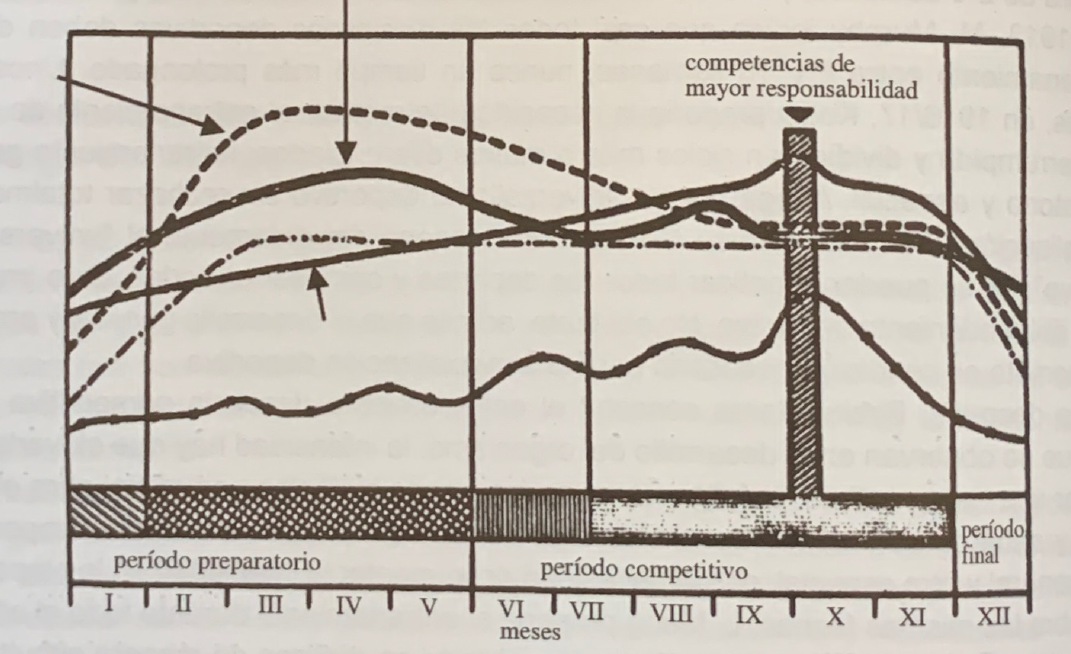

Figure 1, General scheme of Ozolín’s proposal (years 40-50).

In 1950, Letunov gave a scientific advance to the conception of training by considering the biological response as a reference for training planning:

- The planning of training in periods depending on the season (weather conditions, dates of competitions…) is wrong (Ozolín was opposed to this opinion),

- Training must be planned based on changes in training states, that is, biological adaptations. He proposed a test to control the athlete’s fitness that consisted of measuring the heart rate and blood pressure while doing a series of skipping.

Adapting the theories on Selye’s adaptation syndrome, Matveev, in the 50s and 60s, developed a complete training structure for a whole year that he divided into three major ones:

- Form development phase

- maintenance phase,

- Phase of temporary reduction of the form.

Matveev’s influence caused the term “training planning” to be replaced by the term “training periodization”.

The book written by Matveev entitled “Periodization of training” published in 1965, had a great impact among sports technicians around the world because until then there were almost no publications on the subject and because Russian Olympians were achieving great international successes at that time. The success and influence of Matveev’s book was so extraordinary that the term “training planning” was replaced by Matveev’s term “training periodization”.

However, the theories developed by Matveev were oriented towards the preparation of athletes who only had to compete in “optimal conditions” once a year. When the need to compete more times a year increased, these approaches could not respond to the new needs.

From the first conception of training programming or periodization proposed by Matveev we can highlight the following characteristics:

- Many months of “preparation” for a reduced stage of competition with some preparatory competitions and a fundamental one. .

- A very prolonged phase of increasing volume and intensity.

- Much importance to the “general preparation” of “base”.

- Separate conditional and technical preparation.

- Many months without specific training, especially in relation to specific intensity.

- An alleged delayed transfer of the large volume of cargo.

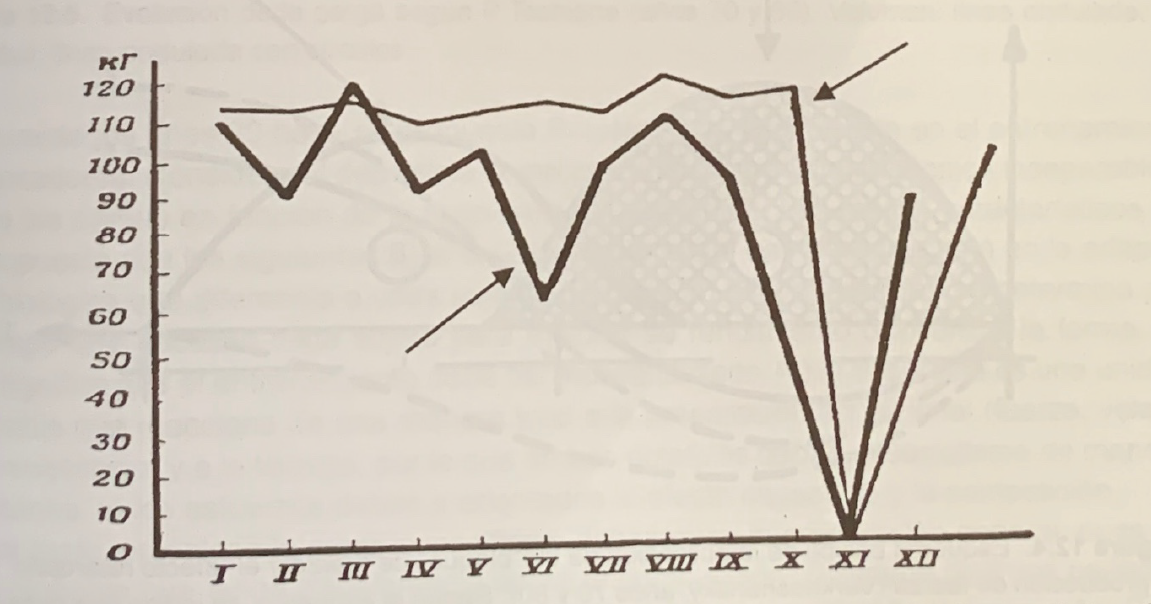

Figure 2. Evolution of the volume and intensity of a year of training (Matveev, years 50-60).

This way of approaching training has led to the creation of certain terminology related to training programming, such as “periodization”, “microcycle”, “mesocycle”, “macrocycle”… This terminology spread throughout the world, although many times there is a great disparity in the extension, interpretation and meaning of each of these terms depending on who uses them. Perhaps one of the most objectionable characteristics of this trend or stage is precisely the “inflation” of terminology coined without adequate justification.

The beginnings of this type of training periodization were popularized by Russian sports scientists and technicians.

The beginnings of this type of training periodization were popularized by Russian sports scientists and technicians. Periodization consists of the distribution of training sessions and recovery periods between said sessions in order to obtain an optimal improvement of the brand at a specific time of the year. Matveev’s proposal has undoubtedly been the The best known and the one that has had the most influence, although it has been losing importance remarkably in the last 20-30 years.

Most of the proposals elaborated later have been made almost in opposition to Matveev’s approach, with the intention of overcoming its deficiencies. The weak points that have been proposed in recent years about the theories of this type of planning are that these theories are merely speculative, not at all quantifiable and full of stereotypes.

Horwill (1992) points out as an example of inconsistency that these theorists frequently insist in their writings on the importance of obtaining the peak of shape at the right moment, but never point out the practical way to obtain it. It also indicates that the language used in training planning theory is often difficult for athletes and coaches to understand because the nomenclature is complex and the language imprecise.

Horwill (1992) writes an article entitled “Periodization — Plausible or piffle”. This author points out what is usually understood when speaking of the following terms: “macrocycle”: between 1 and 4 years (we would say that the time interval considered may be even longer), “mesocycle”: between 1 and 3 months (also here the interval could be extended) and “microcycle”: between 1 and 7 days (here also the interval could be extended) and indicates that the main criticism that can be made of these theoretical bases of training planning is that said Theories are not scientifically proven or have any biological basis.

By ignoring the biological mechanisms of training and recovery, many of the theoretical concepts of training planning become mere conjecture and speculation and unfortunately, according to Verkhoshansky, in various writings, have been treated as infallible dogma.

Ignoring the biological mechanisms of training and recovery means that the theoretical concepts of training planning are conjecture

This criticism of this author may be correct, but there is no known “very scientific” alternative on his part. Since there are no scientific bases, the terminology of training planning is full of contradictions and suffers. Other training planning theorists, such as Arosjev, Vorobiev, Tschiene, Boiko, Bondarcuk during the 1970s and 1980s developed, modified and criticized Malveev’s theories.

These modifications have basically consisted of the following:

- Decrease the duration of the “general conditioning” phase.

- Increase the importance of specific training.

- Perform multiple phases and “macrocycles” throughout the year instead of all three phases in a single annual Matveev “macrocycle”.

- Concentrate very intense training sessions in phases lasting a few weeks.

- Take into account the specific characteristics of each individual and each sport when planning training.

Therefore, starting in the 70s, some alternative ways of approaching training have been proposed.

Arosiev, a disciple of Matveev, proposes a smoother transition from the conditioning phase to the technical part, gradually passing from one to the other, which is why this structure has been called “pendular”. The basic characteristics are:

- Systematic pendulum alternation between general and specific load, with an increase in the specific load and a decrease in the general one as the competition approaches,

- Progressive decrease in the general volume of load while increasing the intensity of the specific load until the competition,

- Training not yet individualized,

- Attempt to achieve transfer of the general load to the specific capacity,

- Conditional and technical preparation separately, vi) frequent recovery periods. Although an attempt is made to adapt to some extent the previous approaches, the characteristics iii), iv) and v) would not currently be considered appropriate.

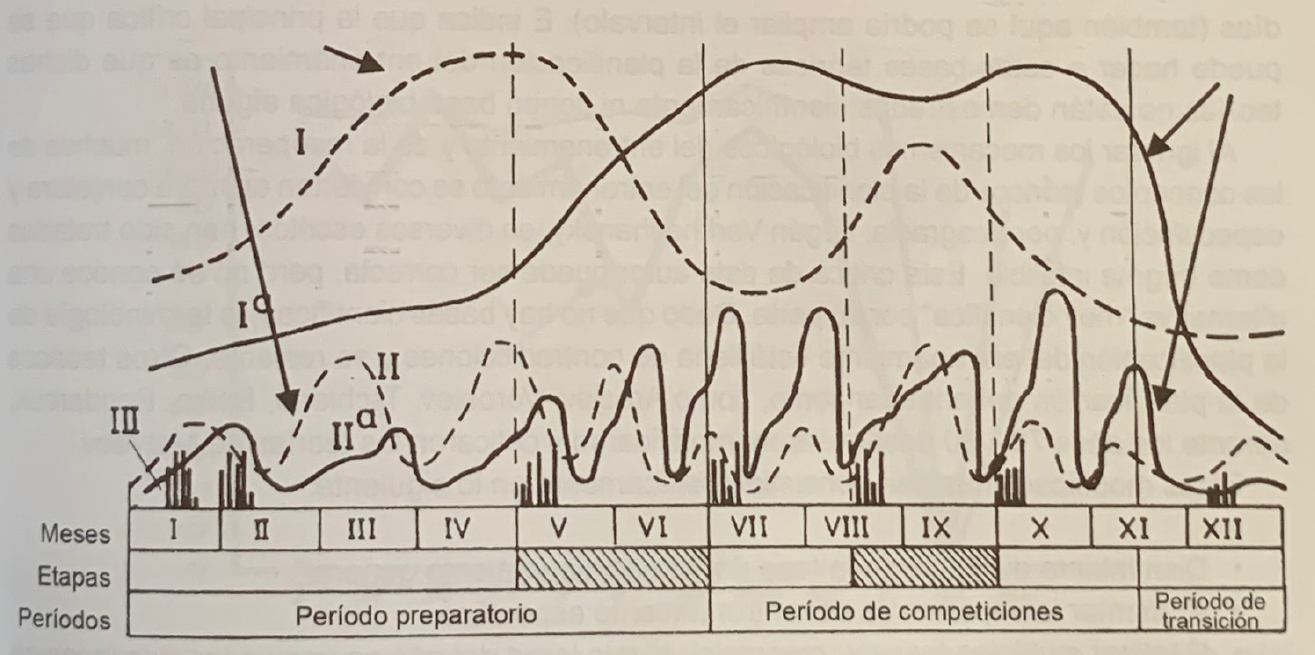

Also in the 1970s, Vorobiev, a doctor, world champion in weightlifting, and coach of the USSR national team, was one of the forerunners of double or triple annual “periodization.” The most characteristic of his approaches is the following:

- Constant alternation of volume and intensity,

- Phases or short periods (approximately one month) of load increase and decrease in order to avoid negative adaptation due to load stability,

- The point of reference is biological adaptation,

- The workouts are very specific.

- Conditional preparation and technique develop simultaneously (especially in weightlifting),

- Specially designed for strength training.

These approaches could be applied today, although the load values in strength training would be lower than those applied to weightlifting specialists.

Figure 3. Evolution of volume and intensity of a top-level athlete (weightlifter) (Vorobiev, 70s).

Verkhoshansky proposes working in specific “blocks” for the development of strength followed by other “blocks” of “strength-technique”

At the end of the 70’s and during the 80’s, Verkhoshansky makes a proposal oriented mainly to the sports called “strength-speed”, but which later extends to most sports specialties. This proposal indicates that strength must be worked on in specific “blocks” for the development of strength followed by other “blocks” of “strength-technique”.

This decision is due to the fact that “maximum force” training is temporarily negative for technique and, therefore, if “maximum force” training is stopped for a while, the effect of this training will remain for several weeks or months and at the same time it will be possible to improve technique and speed and improve sports results.

The justification for this proposal may be based on an error determined by the type of training carried out to improve “maximum strength”, both in volume and intensity. If the training done for “maximal strength” improvement is very heavy: high volume and intensity, it will likely (almost certainly) interfere with technique or any other type of training, but if the strength training does not produce excessive fatigue, the separation of “strength” and “technical” training is not justified.

The characteristics of the proposal are the following:

- The objective of the training to which it is intended is to improve “muscular power” (as we have explained extensively, there is no improvement in “power” without improvement in strength),

- There are phases or “blocks” aimed at improving the “maximum strength” of 1-3 months and “blocks” of “strength-speed-technical” of a similar duration or somewhat longer,

- A certain separation between conditional and technical preparation is maintained,

- Although there is some overlap between both objectives due to the application of exercises that can influence strength and technique,

- An individualized proposal is not yet considered.

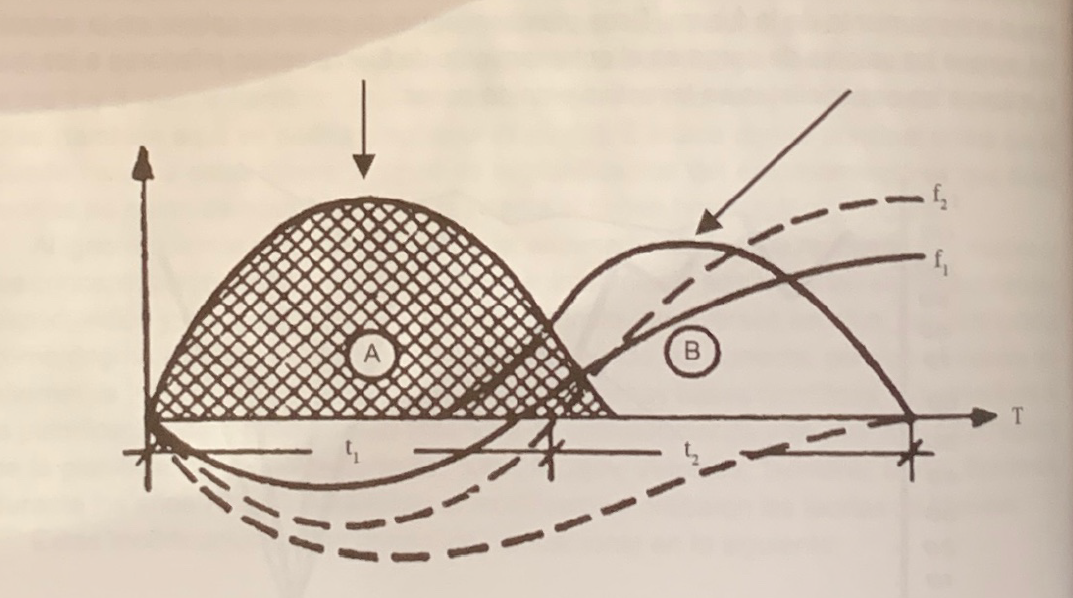

Figure 4. Basic scheme of the application of a “block” of force and the “delayed effect” so: the production of force (Verkhoshansky, years 70 and 80). According to the scheme, it is indicated that there is an optimal loss of force (the so-called explosive force, f-1…) during the force block so that afterwards there is a greater “delayed effect”.

Tschiene proposes a training characterized by maintaining a very high intensity throughout the year

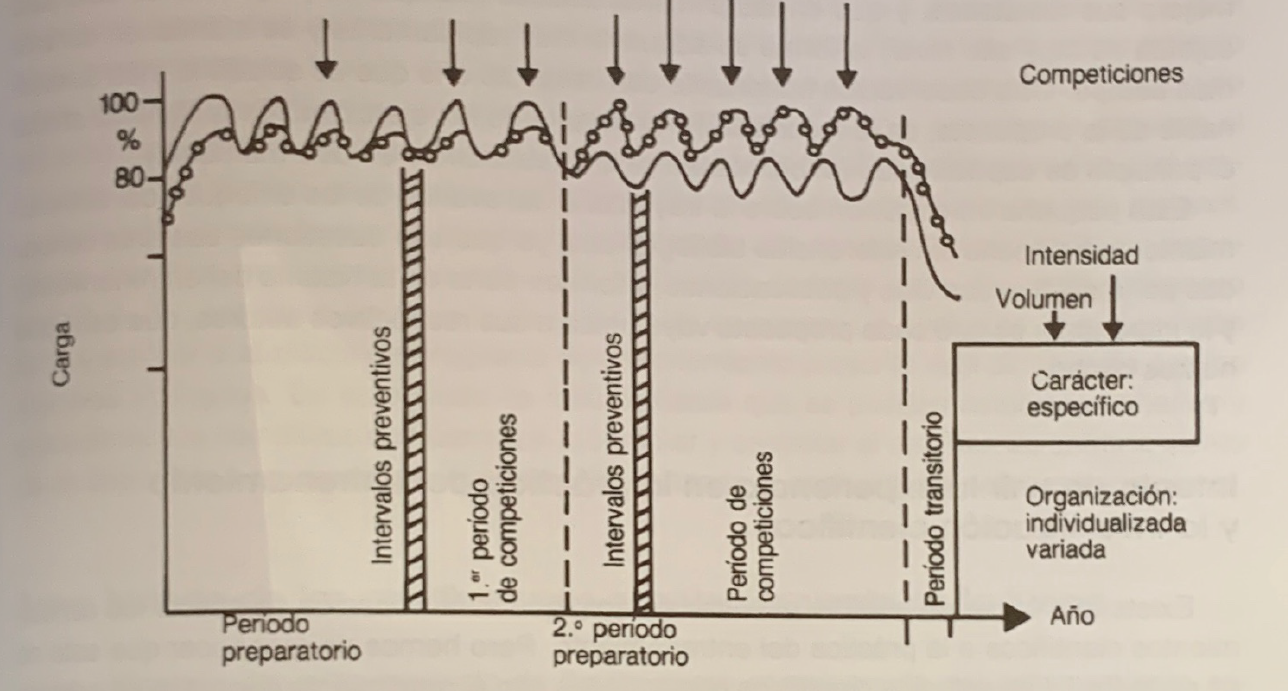

On the same dates, the German Tschiene proposes a workout characterized by maintaining a very high intensity throughout the year:

- The load, volume and intensity, are maintained throughout the year at very high values,

- Introduces a recovery period “prophylactic interval” after the preparatory period and before the competitive, and even within the competitive,

- Participation in a large number of competitions is proposed with the intention of maintaining a high intensity and developing and maintaining form,

- Special and competition exercises are mainly used.

These orientations are mainly adaptable to sports with a high demand for strength and speed and with two big events a year.

Figure 5. Evolution of the load according to P Tschiene (years 70 and 80). Volume: wavy line. Intensity: wavy line with circles.

During the 80s, Bondartchuk, a specialist in the training of pitchers, made his proposal. It considers the athlete as an inseparable conditional-technical unit and adjusts the loads based on the athlete’s response. The characteristic features of his proposal are the following:

- The fundamental criterion of reference is in the biological adaptation that differentiates some subjects from others,

- This adaptation is determined by the time each subject needs to improve their performance or achieve fitness,

- This means that training must be individualized,

- The athlete is an indivisible unit that reacts in a total way to the conditional preparation (strength, speed, resistance) and technique, so both objectives must be developed simultaneously,

- The efforts must be oriented to the specific effect and the competition.

Bondartchuk raises the disappearance of the general preparation since it is unlikely that he will have a transfer on the competition

Therefore, the specific load prevails and the general preparation disappears, since it is unlikely that it will have a transfer on the competition. It distinguishes different periods of adaptation according to the characteristics of the subjects, from 2 to 7 months or more. This means that an equal annual scheme for all subjects disappears.

The most talented subjects will be those who need two months to get in shape, maintain it for one month and lose it progressively the next. After this period and a rest period of 1-2 weeks the process starts again. These periods of 2 + 1 + 1 can be prolonged in other less talented or older subjects.

He proposes a constant change of exercises between 20 and 50%. Beyond this percentage it is not recommendable. These approaches, which seem to be the most complete and perhaps the most accurate of all those exposed, do not take into account that the periods to reach the form necessarily have to lengthen as the subject, even the talented one, improves their results, and that in the early ages (although his proposal is only for very high-level subjects) the form is acquired very quickly and is maintained for a longer time.

Another important observation regarding what is perhaps the most questionable of the proposal is the constant modification of the exercises. This means forgetting the principle of specificity.

This introduction on the trajectory of the advancement of training approaches has been made without bibliographical references, since they are quite well-known issues through many different channels and publications, and they are part of the history of training and the important thing is that each proposal is linked to their respective authors, which is what has been done.